Tickets to the KBA ceremony are sold only as part of the IBC Big Blue ticket package, available online at www.Blues.org or by calling 901.527.2583. The IBC weekend, commencing Wednesday, January 20, 2010, is sponsored in significant part by ArtsMemphis, bandVillage, Beale Street Merchants Association, Budweiser and its local distributor D. Canale Beverages, FedEx, Gibson Guitars, Legendary Rhythm & Blues Cruise, Memphis Convention & Visitors Bureau, Smokin Bluz, Tennessee Arts Commission, and Tennessee Film, Entertainment Commission.

Media sponsors include Beale Street Caravan, Big City Rhythm and Blues, Blues Festival Guide, Blues Revue, BluesWax, Downtowner, House of Blues Radio Hour, Living Blues, Memphis Flyer, WREG-TV, and Sirius XM Satellite Radio B.B. King’s Bluesville.

BIOGRAPHIES OF RECIPIENTS:

Art and Photography: Michael Maness, Memphis, Tennessee

Michael Maness colors his world in blues. His vibrant impressions of Arthur Williams and Luther Allison provided the basis for the 2006 and 2007 Blues Music Award posters, but his gallery of blues performers and musicians is a bold collection of everyone from B.B. King and Buddy Guy to Elvis and Brother Ray. His love of Memphis and its music is evident in the paintings and posters that feature Sun Studios, the Peabody, Isaac Hayes, Stax, Al Green, and Willie Mitchell. From the age of eight, Michael has been drawing or writing something for somebody. “I try to pick a story to paint rather than a moment passing through time. I hope that as a person views my work they feel a story, one that has a beginning, character development, a problem to solve, and a happy ending.” With his dynamic kaleidoscope of colors, Michael lets his paintings tell Pulitzer Prize stories.

Blues Club: Bradfordville Blues Club, Tallahassee, Florida

It may be the coolest juke joint experience outside Mississippi. Drive down a secluded dirt road through fields of cornstalks and massive Spanish-moss-covered live oaks until you see the glowing, cinder block juke in the distance and you’ve found it. Featuring live blues every Friday and Saturday night since 1964, the BBC has hosted blues royalty like Bobby “Blue” Bland, Bobby Rush, Jimmy Rogers, Pinetop Perkins, Little Milton, James Cotton, Nappy Brown, Ms. Lavelle White, Kenny Neal, Big Jack Johnson, E.C. Scott, Maria Muldaur, Son Seals, and a host of others. When the music gets too hot, you can always go outside to join the crowd surrounding the roaring bonfire (a rarity in today’s world) or listen to the blues from the bonfire stage. New owners Gary and Kim Anton took over the club eight years ago and have worked hard to change little.

Blues Organization: Connecticut Blues Society

Since it was founded in 1993, the Connecticut Blues Society has been at the forefront of blues events and programs in the Nutmeg State. Though most of its events are music related - supporting weekly jams at a variety of Connecticut blues clubs, sponsoring many blues festivals and events, and running the most extensive IBC band and solo/duo competitions - the CTBS is also very active in many service programs. In the past, it has run benefits for the March of Dimes. It also holds two fundraising events each year with the local Hannon-Hatch VFW Post. In addition to its education outreach programs, the CTBS assists with monthly concerts at the Connecticut Veterans Home and Hospital. Because this society covers an entire state, it offers a model of music, history, and community service for any affiliated society.

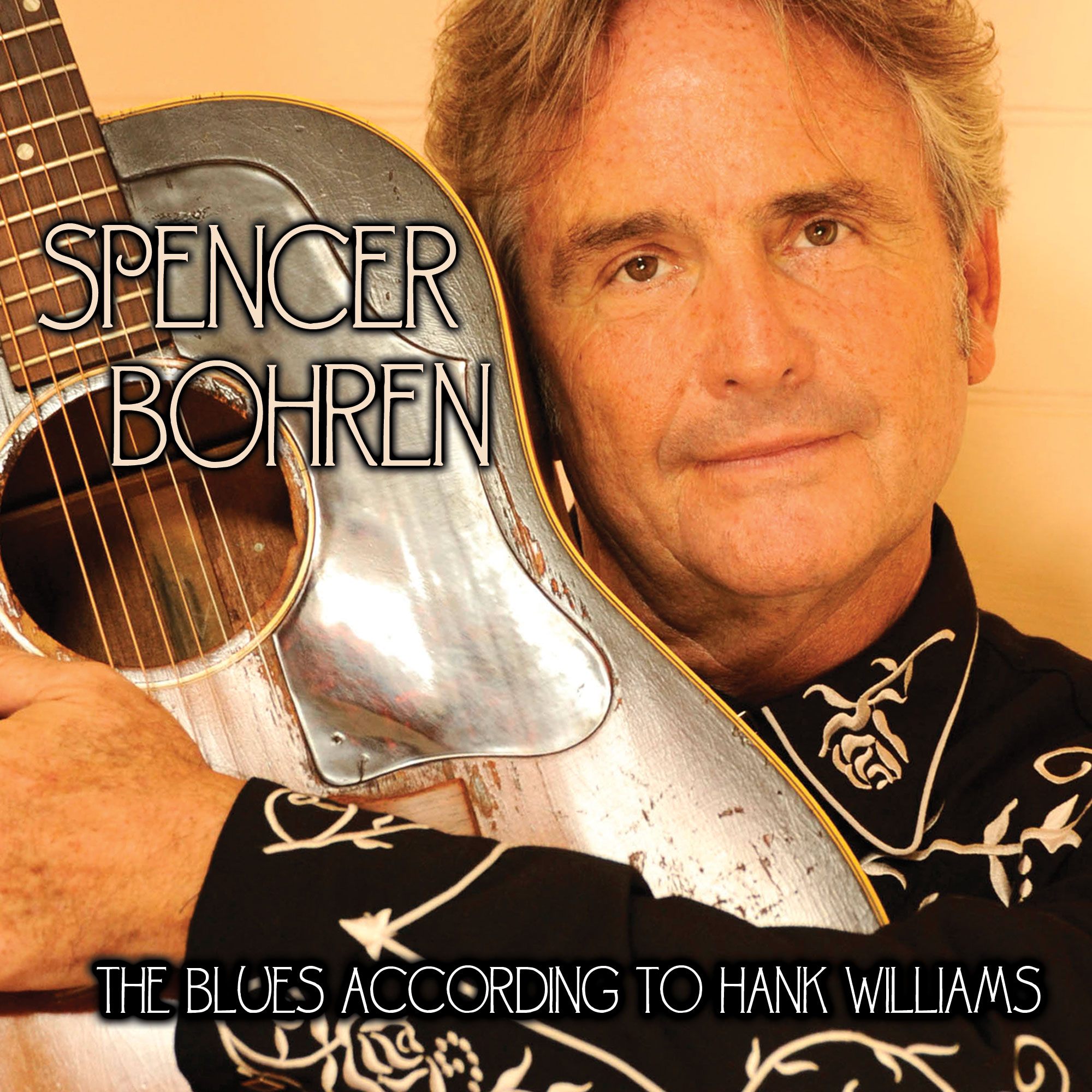

Education: Spencer Bohren, New Orleans, Louisiana

Four decades of international touring and many years of visiting schools have helped Spencer Bohren develop an innovative approach to blues education titled “Down the Dirt Road Blues.” Using a single African melody as a starting point, he follows the song as it travels through America's history and culture, using appropriate vintage instruments to orchestrate his story. The song finds its way into the repertoires of Charley Patton, Son House, the Skillet Lickers, Hank Williams, Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, and the Rolling Stones, among others, before setting a young Spencer Bohren on his life's path. “Down the Dirt Road Blues” was first performed in 1997 for the Montana Performing Arts Consortium and has since been presented to 20,000 students from elementary through university age in the U.S. and Europe. Peggy Seessel, director of education for ArtsMemphis, praised “Down the Dirt Road Blues”: “Every child in every school should be exposed to this fascinating, enlightening story.”

Festival: Heritage Music Blues Festival, Wheeling, West Virginia

The Heritage Music Blues Festival began in 2001 when Bruce Wheeler envisioned a blues music festival in a newly constructed waterfront park on the bank of the Ohio River in downtown Wheeling. The fact that Wheeling had no blues scene or even a blues club, band, or solo artist did not deter Wheeler from developing a festival. Promoted as “A Weekend of Award-Winning Blues,” the festival today gets raves from coast to coast. Wheeler’s festival features two stages, a main stage with Blues Music Award winners and up-and-coming IBC solo, duo, and band acts, and a second stage dedicated to local and regional artists from West Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. The festival is run year-round solely by Bruce Wheeler and his family, so a family atmosphere spills over to the audience members, who have come from 25 states and four countries for the annual August event.

Festival International: Piazza Blues, Bellinzona, Switzerland

Where else can you dance to the music of some of the finest American blues legends in a piazza guarded by three ancient hilltop castles? Amid a jumble of outdoor cafes, trattorias, and medieval churches, the piazza has the feel of an intimate, outdoor blues bar. Since its start in 1989, Piazza Blues has aimed to bring blues music, from its origins up to the present day, to a wide audience. Major blues performers including B.B. King, Albert Collins, Albert King, James Cotton, Robert Lockwood, Jr., Honeyboy Edwards, Koko Taylor, Luther Allison, Charlie Musselwhite, Otis Rush, and John Mayall have performed, and today, 21 years later, festival President Daniele Jorg, Artistic Director Fritz “Big Daddy” Jakober and Vice-President Lucio Robbiani, the son of the festival’s founder, also showcase younger blues talent such as Ryan Shaw, Corey Harris, Diunna Greenleaf, and Shemekia Copeland. Piazza Blues is acknowledged throughout the blues world as one of the top European blues events each summer.

Historical Preservation: Eric Leblanc, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

Eric LeBlanc combined his love of blues, jazz, and discographical data. Though he has been active since 1968 in blues radio in Canada, Eric understood that proper verification of the music’s vital statistics is necessary. Thus he has been collecting and sharing vital data and documentation that have been an essential part of the music books and magazines we read. The print publications Goldmine, Down Beat, Blues & Rhythm, Living Blues, and Juke Blues are some that have relied on his data. Since the early 1990s, he has been providing fans and researchers on various listservs with data to verify performers’ names, important dates, and discographical data. The principal ways to access his work have been through HYPERLINK "http://www.bluesworld.com/" \n _blankwww.bluesworld.com and HYPERLINK "mailto:Pre-war-blues@yahoogroups.com"Pre-war-blues@yahoogroups.com. Since retiring in 2005 from the Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, he has joined the Jazz Faculty of The Victoria Conservatory of Music, teaching the Jazz & Blues Survey courses. In 2010, Eric co-authored, with Bob Eagle, the Blues volume in the Greenwood Press Guides to American Roots Music.

International: Finnish Blues Society, Helsinki, Finland

Starting with Jukka Wallenius' idea of publishing a blues magazine, the Finnish Blues Society has been the blues force in Finland since 1968. Within a few weeks it published the first issue of Blues News, which continues to appear today, 239 issues later. Its circulation is about 1,500 copies, six issues a year of approximately 70 pages. During the late 1960s, the Finnish Blues Society also began to arrange jam sessions for Finnish blues musicians, then concerts with international blues artists, from Champion Jack Dupree, Professor Longhair, and J.B. Hutto in the ’70s to Luther Allison, Long John Hunter, and Johnny Bassett in the ’90s. The society started its own blues label, Blue North Records (originally FBS Records), in 1969, mainly associated with its collaboration with Eddie Boyd, who was living in Finland between 1971 and 1994. Today there are over 900 members who support the magazine, record releases, concerts, and lectures. In 1995, the FBS and Blues News opened their website as an archive for all blues fans in Finland.

Journalism: David Fricke, Rolling Stone, New York, New York

When there’s a story about the blues in Rolling Stone, the byline often reads David Fricke. Though Fricke, now a senior writer, has been on staff at the magazine since 1985, he has written about music in a variety of other outlets including Mojo, Melody Maker, Musician, and People. As a senior writer, Fricke’s stories can be about newcomers such as Derek Trucks or John Mayer where he illuminates their blues roots, or a cover story like “Blues Brothers,” an interview with Keith Richards and Jack White where each articulates his blues core. Fricke reviews everything from Jelly Roll Morton to the newest cutting-edge band on the scene, but always with an ear to the blues. For Fricke, blues is ground zero, the earthy beat that connects the music of past rockers like Led Zeppelin to today’s mega-popular Green Day. The taproot of his stories is his awareness that blues is an important part of the foundation of American music. Making those important connections is an essential part of the stories he tells.

Literature: Crossroads: The Life and Afterlife of Blues Legend Robert Johnson, Tom Graves, Memphis, Tennessee

Tom Graves has taken the most widely known pre-war blues performer, Robert Johnson, and chipped away at the widespread myths that have been associated with this blues legend. For example, Graves tackles the various ideas associated with Johnson’s strychnine poisoning at a juke. Graves took that idea to a toxicologist for answers. The book offers a condensed look at Johnson’s life, style, songs, death, and after-death fame. Chapters cover the period after the recordings were released in 1961 on Columbia, the lost photos, the 1986 movie Crossroads, the 1990 release of the million-selling Sony Legacy Complete Recordings boxed set, and the paternity case that discovered his son, Claud. Graves’ book is the easiest way to enter the tangled world of Robert Johnson. From there, and through his extensive bibliography, each of us can conduct his own Robert Johnson inquiry.

Manager: Pat Morgan, Kailua-Kona, Hawaii

Dr. Patricia Morgan has been involved with the blues community since her early 1980s work with local musicians, venues, and festivals in the San Francisco Bay area. Pat began working with Pinetop Perkins in 1996 during a difficult time in his life. Within a year, Pat was able to turn his life around. Since that time, under Morgan’s guidance Pinetop has received six Grammy nominations. In 2000 he received the National Endowment of the Arts Fellowship Award, and he was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2003. He received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005 and won a Grammy in 2008. Ten years ago, Morgan also created the Pinetop Perkins Homecoming Jam at Hopson’s Plantation in Clarksdale, Mississippi. Recently Morgan started the Pinetop Perkins Foundation, a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to helping young musicians at the beginning of their careers and helping older musicians with respite care at the end of their careers. Since 2005, Morgan has been doing the same job for Willie "Big Eyes" Smith, helping him transition successfully from drums to harmonica. Leading his own band, with two well-received CDs, Willie Smith has a revitalized career as evidenced by BMA first in 2009, nominations in both Instrumentalist-Harmonica and Instrumentalist-Drums.

Print Media: Block, Almelo, Netherlands

What began as a small fan magazine in 1975 has grown into one of Europe’s finest blues magazines. Block (the name is an amalgam of “blues” and “rock”) was first published 35 years ago by Rien Wisse and his wife, Marion, in the Netherlands. Like most of these efforts, the magazine is financed primarily by their love of the blues and their own money. In 1982, Rien dropped rock coverage and turned Block into the Dutch blues magazine. The magazine is published four times a year and features articles written by American blues journalists such as Bill Dahl, Dick Shurman and Scott Bock. The beautiful photos are part of Block’s 30,000-photo file, which dates back to the magazine’s early days. Is 64 pages concentrate on profiles, reviews of records and performances, and the Wisses’ travels throughout the American blues landscape.

Producer: Andy McKaie, Santa Monica, California

Andy McKaie wasn’t in the Chess studios when Leonard and Phil recorded Muddy, Wolf, Walter, Etta, Bo, Chuck, and others. But since 1986, he has shepherded hundreds of Chess and other Universal/MCA blues reissues. As senior vice president of A&R for Universal Music Enterprises, McKaie has been the man at the controls for virtually all of the reissues, compilations and box sets from the catalogue of Chess recordings. He has also been the producer of numerous other Universal Music blues collections, the Chess 50th Anniversary collections, the Millennium, Definitive and Gold collections, the Martin Scorsese Presents the Blues series, and, most recently, the Hip-O Select series of complete Chess Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, and Little Walter sets. As the producer of these classic recordings, McKaie conceives the project, selects the tracks and masters, mixes multi-tracks, and researches the credits. In addition to the 21 Muddy Waters reissues he’s responsible for, McKaie has had a production hand in 18 B.B. King records, including co-producing B.B.'s Blues Summit album and co-executive-producing the blues legend's 80 set. From Muddy to B.B. and everybody between, Andy McKaie has kept hundreds of blues records alive.

Promoter: Pozitif Productions, Istanbul, Turkey

Can you picture Bobby Rush in 20 different Turkish cities performing his signature chitlin-circuit show? For 20 years, Pozitif Productions has been promoting a blues tour called the Efes Pilsen Blues Festival, which runs for over 30 days with more than 20 shows throughout Turkey, and sometimes overseas in countries such as Russia, Serbia, Romania, and even Kazakhstan, with the support of Turkish beer company Efes Pilsen. Based in Istanbul, Pozitif is dedicated to developing music audiences through its festivals, live music venue, artists, albums, and concerts spanning a broad spectrum of music encompassing all world styles. When Ahmet Uluğ, the blues festival director and co-founder of Pozitif, books American blues acts, he does it so that he can bring international blues musicians together with local artists. This year Shemekia Copeland, Terry Evans, and Ray Schinnery spent six weeks as the featured performers, but the 20-year roster includes Shemekia’s dad Johnny Copeland, Kenny Neal, Honeyboy Edwards, Magic Slim, Nappy Brown, Buckwheat Zydeco, Gatemouth Brown, and many others. Every musician who has experienced Turkish hospitality raves about the first-class treatment during the weeks abroad.

Publicist: Richard Flohil, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

For more than 50 years, Richard Flohil has been committed to the blues. As a concert promoter, he was involved with the first appearances in Canada (in the late ’50s and early ’60s) of Sleepy John Estes, Robert Nighthawk, Muddy Waters, Bobby Bland, and Buddy Guy, among others. He started his first publicity company, Richard Flohil and Associates, in 1970. In the years since, he has handled the Canadian publicity for Canada’s leading blues and roots-music record label, Stony Plain Records, whose roster includes Duke Robillard, Maria Muldaur, Amos Garrett, Ronnie Earl, Big Dave McLean, the late Long John Baldry, and others. Some of his current clients include Shakura S'Aida, Roxanne Potvin, Paul Reddick, Treasa Levasseur, and the estate of the late Jeff Healey, for whom he worked for five years; Flohil also handled publicity for Canada’s Downchild Blues Band for 39 years. Flohil served on the board of the Toronto Blues Society for 12 years, and remains a member of its programming committee. He continues to work as a club and concert presenter.

Radio (Commercial): Charles Evers, WMPR, Jackson, Mississippi

Born in Decatur, Mississippi, in 1922, Charles Evers has been an ardent advocate of civil rights and equality. In 1969 he was elected mayor of Fayette, Mississippi, and was named the NAACP’s Man of the Year. Since 1987, Charles Evers has been the station manager for WMPR. He launched a career in radio as a disc jockey at WHOC in Philadelphia, Mississippi, in 1949-50. Daily programming includes blues shows every morning from 5 to 9 A.M. and every afternoon from 4 to 8 P.M. In addition to overseeing the station’s daily blues segments, he also hosts the weekly talk show Let’s Talk. For 46 years, Charles Evers and B.B. King have promoted the Medgar Evers Homecoming Festival, a three-day annual event held the first week of June in Mississippi. This event features parades, gospel festivities, and a blues show to celebrate the life and work of his brother, the assasinated civil rights activist Medgar Evers.

Radio (Public): Rick Galusha, KIWR-FM, Omaha, Nebraska

For the past 20 years, Sundays have been blues days in eastern Nebraska and western Iowa. Pacific Street Blues is a long-running radio program that focuses on blues and Americana music and airs every Sunday from 9 A.M. to noon on 89.7 The River. The show is still hosted by its creator, Rick Galusha. In addition to programming a wide spectrum of blues, Galusha has hosted many legends such as B.B. King, Johnny Winter, Dr. John, Luther Allison, and others in the studio. He’s a major supporter of the Omaha Blues Society and its Kids Ed program. In addition to his work on radio, Galusha is instrumental in booking and promoting shows including artists like Rod Piazza, Sue Foley, Coco Montoya, Indigenous, Bernard Allison, and many other household blues names. As the former president of Homer’s Music Stores, Galusha supported blues in retail; he still writes reviews for BluesWax ezine.

Record Label: CrossCut Records, Bremen, Germany

CrossCut Records was founded in 1981 by owner Detlev Hoegen with the goal of promoting the blues in Europe. In 1984, CrossCut was the first record label to release a set of previously unissued live radio recordings by the late, great Freddie King. Rockin' the Blues – Live was released by special agreement with the King estate and won a W.C. Handy Award in the category Best Contemporary Blues Album of the Year. The list of artists who have recorded for CrossCut reads like a who’s who of the blues: Terry Evans, Jimmy Rogers, Otis Clay, Charlie Musselwhite, the Nighthawks, Mighty Sam McClain, Sherman Robertson, Sharrie Williams, John Mooney, Roy Gaines, Ronnie Earl, and many others. CrossCut has also released a 7-CD set of live recordings called In the House: Live from the Lucerne Festival. Today, it features current recordings by Philipp Fankhauser, Memo Gonzalez, JW-Jones, and B.B. & The Blues Shacks.

Visual Broadcast: Film, Television and Video, Pocket Full of Soul

Everyone in the blues has a journey to talk about. For director Marc Lempert and producer Todd Slobin that journey centered around the harmonica, a staple of the blues. Their journey - more like an odyssey - took them deep inside the instrument, its players, and its culture. They, like others who have embraced the harmonica and made it a part of their lives, soon discovered the power and mystery of the instrument. Since the harmonica is the only instrument where one has to breathe in and out to produce sound, it forms an undeniable connection to the player as it captures the body and spirit of each individual who puts it to his mouth. With Huey Lewis as the narrator, the film travels the world to illustrate the instrument’s history, ubiquity, and present impact. The interviews, stories, how-tos, and performances by masters such as James Cotton, Charlie Musselwhite, John Popper, Magic Dick, Lee Oskar, Rick Estrin, Delbert McClinton, Jerry Portnoy, Kim Wilson, and Jason Ricci are thrilling enough to get you to find that old Marine Band and start drawin’ some blues riff on the reeds.

<i>The Blues Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization dedicated to preserving Blues history, celebrating Blues excellence, supporting Blues education, and ensuring the future of this uniquely American art form. It is the umbrella organization for a worldwide network of 180 affiliated Blues societies and has individual memberships around the globe. In addition to the Keeping the Blues Alive Awards, The Blues Foundation produces the Blues Music Awards, the Blues Hall of Fame Induction, and the International Blues Challenge. For more information on how to support The Blues Foundation check us out on the web at www.Blues.org.